Quest for Fire

- Quest for Fire

- About Quest for Fire

- Quest in pictures

- Quest on video

- Anthony Burgess: Talking Animal

- Quest in the news

- Quest for Language

- Quest in Audio

- Quest for trivia

Quest for Language:

Quest for Fire: inventing an ancient language

The languages invented by Anthony Burgess for Jean-Jacques Annaud’s 1981 film Quest for Fire (French title: La Guerre du Feu) are not as well known as they deserve to be. One reason for this is because the film contains no subtitles: the challenge for the viewer is to learn the unfamiliar languages spoken by the main characters by ear alone. Another reason is that much of the work undertaken by Burgess did not survive into the final cut of the film. The ‘Ulam Dictionary’ created by Burgess is considerably more extensive than viewers of the film might have imagined.

The Burgess archives in Texas and Manchester contain a range of materials which document the creation of ‘Ulam’, the main language spoken in the movie. The commission from Annaud was to make a speculative reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European (known as PIE), the ancient language thought to be the ancestor of modern European languages, which does not survive in a written form.

Although Burgess was originally asked to devise two languages of not less than sixty words, the final version of Ulam runs to more than 160 words. It seems that he was excited by the opportunity to develop a complex language, and he delivered more than he had been paid for.

The surviving papers indicate that the Ulam Dictionary went through at least three major revisions, and that Burgess’s languages were constructed and revised over a period of around ten months.

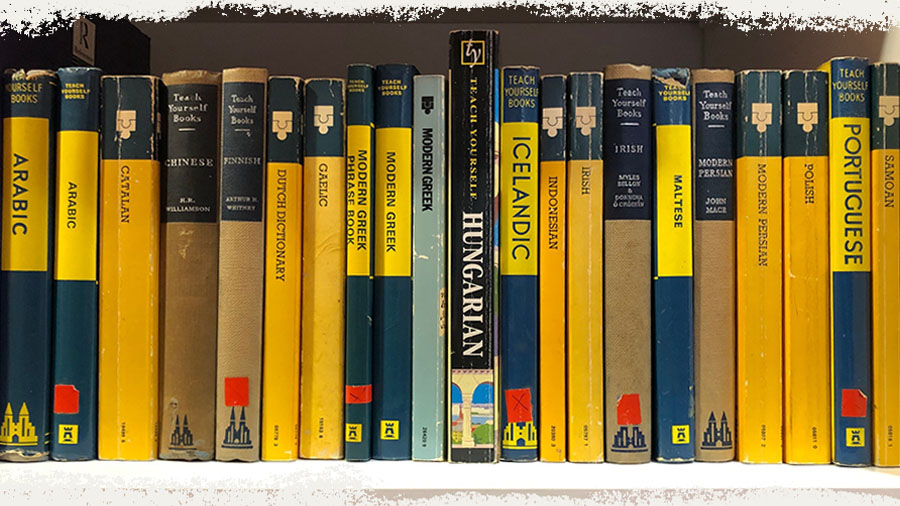

Burgess began his research by consulting some of the books he had studied as an undergraduate student at Manchester University in the 1930s. He relied quite heavily on the account of the evolution of Indo-European languages given by Otto Jespersen in his book Growth and Structure of the English Language, published in Leipzig in 1930. Burgess also consulted his collection of ‘Teach Yourself’ language books which are now part of the Foundation’s book collection. The surviving volumes document his wide-ranging study of modern languages such as Dutch, Gaelic, Greek, Hungarian, Icelandic, Persian, Portuguese, Spanish and Turkish.

When it came to constructing the ‘new’ languages for Quest for Fire, drawing on a variety of linguistic roots, Burgess combined elements from Indian, Armenian, Hellenic, Albanian, Italic, Balto-Slavic, Celtic and Germanic languages. He paid special attention to Sanskrit, on the basis that this was ‘the oldest surviving language of the Indo-European group,’ and because T.S. Eliot had included a handful of Sanskrit words in his favourite poem, The Waste Land.

His method was based on the traditional comparative philology he had been taught as a student. Looking at the word for ‘father’ in various modern languages, he found ‘vater’ in German and Dutch, ‘pater’ in Latin, ‘pitar’ in Sansrkit and ‘faðir’ in Old Norse. Working from these examples, he concluded that the Indo-European word for father ‘must have begun with a lip-sound, the middle consonant must have been dental or alveolar, and there must have been a terminal r-sound.’ Following these principles, Burgess decided that the Ulam word for ‘foot’ would be ‘powd’ (as in the French ‘pied’ or ‘pedes’ in Latin). Water would be ‘aga’, with the same word used for ‘river’. ‘Dondra’, derived from the Greek ‘dendron’, is the Ulam word for ‘tree’. Fire itself is ‘atra’, related to the English word ‘hearth’.

And yet words are only part of the sign-system known as ‘Ulam’. The other significant element is a series of gestures to accompany spoken words, developed in collaboration with the anthropologist Desmond Morris, author of The Naked Ape and Bodytalk: The Meaning of Human Gestures.

In the final version of the Ulam Dictionary, dated 30 May 1980, physical actions are indicated alongside the words to which they refer. To communicate aggression, there are three different forms of sound and action. Mild aggression is indicated by repetition of ‘Tka, tka, tka,’ with a side-to-side swaying motion. Moderate aggression involves the word ‘Dga, dga, dga,’ with more vocalisation and resonance, and with increased body movement. The strongest and most violent form of aggression is communicated with the words ‘Arr’, ‘Ang’ and ‘Arm’, with the mouth open, the voice coming from the chest, the lips pulled back to expose the teeth, and a dominant stance.

Reading the dictionary gives us a fuller picture of how Burgess thought prehistoric people might have used language. The movie dramatizes his vocabulary and gives the words a shape, combining J.H. Rosny’s novel, Gerard Brach’s screenplay, and Annaud’s visual imagination.

The fortieth anniversary of the film’s release in 1981 was celebrated by a new edition on DVD and Blu Ray — and it is worth remembering that none of the characters in Quest for Fire would have had a language without Burgess’s work of research and speculative reconstruction.

Anyone who studies Nadsat in A Clockwork Orange will want to consider this fascinating alternative example of a language invented by Anthony Burgess.

Andrew Biswell